Danish performance group Hotel Pro Forma: an interview to Ralf Richardt Strøbech, expert in animation and video montage

Hotel Pro Forma is an international laboratory of visual music performance and installations. The structure of the work is strongly anchored in music, visual arts and architecture and does not follow traditional theatrical structures. Since 1985 Hotel Pro Forma has produced more than 50 works shown in over 30 countries, ranging from exhibitions to performances. The artistic director is visual artist Kirsten Dehlholm.

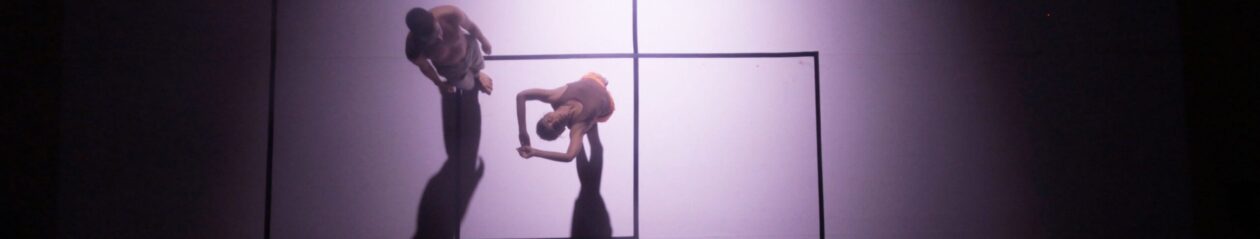

Laughter in the dark. The mind deceives (2014) from Vladimir Nabokov’s novel tells the story through a series of visual and audio effects. The audience experiences how their own senses are influenced and challenged in combination with the main characters. The world seen through the eyes of Charles Darwin forms the basis for the performance Tomorrow, in a year. In War Sum Up. Music. Manga. Machine 12 singers and a striking light design that give a powerful visual impression of the nature of war. Hotel Pro Forma’s striking visuals blend with pop-duo The Knife’s ground-breaking music to create a new species of electro-opera. The performance Cosmos+ will consist of a composition of live performance, projections, optical illusions, light, music, sound and text. Analogue actions and low-technology installations will be combined with interactive monuments and high-technology tools. Relief: a motion picture relief: in this performance that takes place on a two-dimensional screen, the audience is given headphones and taken on a journey to the Ukrainian harbour city of Odessa.Real-life stories based on interviews with the people of Odessa are intertwined with the writings of Nabokov to create a new self-understanding. Through the 3D sound-scape heard only through the headphones, the audience’s perception of 2 and 3D are challenged. Perception and reality are set in relief.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: Which is your personal artistic background and the theatrical and aesthetic models that influenced you and when you decided to be a part of the group?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH. Kirsten Dehlholm founded Hotel Pro Forma in 1985, I have been with HPF since I graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture, in Copenhagen. That will soon be five years since.

Back in the 90s, I worked briefly as an opera singer, and was in that way connected to the performance Operation: Orfeo, that toured already back then. Some years ago I was appointed artistic director, working closely with Kirsten on conceptualizing and directing the pieces, working also with stage design.

I have always been drawn to aesthetics that relied more on structure, texture and space than on psychological narrative, since I believe that it is better to make room for multiple emotions and comprehensions than to project them specifically. The somewhat abstract narration that exists in architecture is actually also my ideal in theatre.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: In your productions with Hotel Pro Forma theatre, film, video, light, music, images are conciliated in an ideal unicum dramaturgy; how do you project this type of multimedia performance: beginning from a previous text or mixing all your sources creating a performance text after the rehearsals only?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: Each performance has a different point of departure, or rather points of departure. It could be an existing text or fragment, a social condition, an existing space, a technology, a philosophical theme, or even a person. Sometimes combining two or more seemingly detached points of departure creates a space for navigation that is very productive. In the special case of the Relief-performance it was geopolitical and cultural changes in Eastern Europe that created the point of departure, but this was quickly combined with texts by Vladimir Nabokov and binaural (3D) audio technique to provide the right balance of supporting and contradictory elements to create a multilayered performance.

You are quite right in saying that the actual goal of the performances is to create exactly this unicum dramaturgy of separate elements. The finished piece tries to strike a balance between internal logic and external representation. A sort of world-building with opinions.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: Could you tell about the steps of a digital creation according to Hotel Pro Forma? And is there a single language which has more importance than the others?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH. Creating art in digital media very often is a problem of creating enough information to refer to external reality. Relief works with two kinds of digital creation, audio based and visual. In both cases the goal is to investigate the informational relief between the artificially created and the passively recorded.

Consider being in a street full of urban noise with your eyes closed. There would be a tremendous amount of information, cars, people talking, wind, animals, brooming of fallen leaves and putting up tables outside cafés. There would also be a fundamental acoustic situation that somehow portrayed the configuration of surrounding buildings as well as materials and even the position of the person listening. Normally your perception sorts out this chaos and points you to hear what you need to hear the most, e.g. to avoid being hit by a car or to spot your friend in the crowd. When you record reality to use in a performance, you need to do the cleaning up of reality in order to make the spectator hear something specific/intended. Now, creating this situation digitally from scratch is somehow the reversed situation. How do you get enough information into the rendering to make it reveal something other than its construction? How and what to put into the “image” to make it communicate what you want, perhaps even to approach itself to a “realistic” or multifaceted representation? This is really the subject matter of relief, exploring the gap between the recorded and the created, between too much and too little. In the case of visuals, I try to de-animate video, and to animate still photos, trying to see what happens to representation of reality as they approach.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: In Italy the digital performance as a genre is considered not so positive, too much “alternative”, nearer to visual arts than the theatre, so that the official theatres schedule very few digital projects. Is it that way also in Denmark?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: It is very unfortunate that the distinction between visual arts and theatre is stressed so much, really it is to the benefit of no one. It would be much better if artists made pieces that drew on the means accessible – in the right way, at the right time, and for the right reasons. Unfortunately production realities, theatre profiles and audience expectations do not support this way of thinking, most people like to have an idea about what they will get before going to see something, also in Denmark. But it would be much better for everyone if we could gradually develop a broader attitude toward experiments and curiosity, going to the theatre to wonder and think together in the meeting between the artists and the audience through the performance.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: In Denmark does it exist a centre or a place for artistic researches in interactive media applied to the Theatre and doesn’t it exist any festival dedicated to them?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: As far as I know, there is no such place in Denmark. But it is very possible to work in mixed media on more traditional venues, and it is definitely possible on some of the open stages that exist. And it is not looked on as too “alternative” as such, but it definitely isn’t part of the mainstream either.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: Which are the most important examples of international digital performance group, near to your artistic experience?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: I have really tried to figure out what to answer to this question, and I can’t really make my mind up. Naming any one group or person would somehow point in a direction, indicating the future of digital performance in general. But I really believe that the future lies in individual experiments, not connected with style and tradition or any one practitioner. Around the world, interesting things are going on, this is a field still very much in progress. Still, with this in mind, I could mention the Croatian group BADco whom I have met and seen on various festivals around Europe, and the Italian group Ortographe. I don’t know whether their work can be classified as digital performance as such, but it is certainly extremely interesting and points toward the future even if it does it with and through the past. Another extremely interesting artist is Tony Dove, based in New York, who really does an amazing job pushing the limitations of interaction in narration. But in every work of art, if done with sufficient care, love and brains, there will be something to investigate further and to fertilize your own imagination. Canonical answers just make everybody stare in the same direction, thus missing what is behind them.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: In a first glance some of your shows are similar as a structure to some of the best theatre pieces by Bob Wilson: as a matter of fact also in your works lights and images (and sounds) make the space and also Wilson began in architecture. Is it correct this parallelism? Which is the relationship between theatre and architecture in your show?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: Architecture is the most important art form. It shapes our entire understanding of the world by giving us a space from which to look back onto the world. It is in this sense that the performances are architectural, they provide a platform for understanding much bigger issues. Understanding theatre as a form of architecture also liberates me from the linear dramaturgy of the progressive narrative, it is no longer a corridor with rooms on the side, but rather a free-flowing movement through inter-connecting spaces of meaning and ambience. Architecture is structured liberty, perhaps Robert Wilson would agree on this.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: Steve Dixon speaks about Augmented Stage for describing multimedia theatre. Is it correct as definition?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: Unfortunately, I don’t know his theory, but the term Augmented Stage certainly sounds intriguing. The use of other media allows for different connotations altogether, new and old traditions are brought to the table. It means new possibilities for contextualizing, expanding the on stage as well as the off stage, and allows for treating time and space with more freedom and plasticity.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: How the rules of the director and the function of the actor and of the collaborators (and also of the audience) are changing in this new forms of theatre? Is it right to affirm that in a digital perspective the theatre is becoming more and more a collective creation?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: Actually, I don’t think that the role of the director changes very much. Directing is a very personal matter, so how it is done is not depending on the used media so much as it is defined by the personal style and the subject matter at hand. Since using digital media is very often a very slow process (just think of the painstakingly slow business of frame by frame animation!), it involves “directing” the collaborators more in the pre-production, requiring a more defined idea to begin with, so as to not waste too much time as the deadlines approach. Digital art forms as a rule do not lend themselves easily to improvisation, at least not in my experience. Much effort is put into the technical aspects of the production, to make live feeds have an acceptable resolution, edited material to have the right relationships to the performance as a whole, and so on. The risk is, of course, that the performers slide to the background in this technical mayhem. The fact is, that no matter how much expression new media can bring to the stage, the performer almost inevitably provides the point of entry for the spectator, since identification with a person is so much easier than identification with, say, a vacuum cleaner.

As to the collectiveness of the digital performance, it really depends on how much technology you know yourself. If you know nothing of the possibilities at hand, you are clearly at the mercy / in the good hands of the person actually executing the required task, which can be a bad or a good thing respectively. The amount of collectivity has almost nothing to do with the medias used, it is only connected to the creative process and to how well you know and trust your team.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: Which is the relationship between your works as installations and the theatre pieces? The spectator is involved in the work in the same way?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: The most fantastic thing the classical theatre has brought the world, is to engage the audience emotionally in an almost unbelievable way, just think of the excruciating agony in Romeo and Juliet, the exuberant joy in The Tempest, the fathomless hopelessness in Uncle Vanya. The best thing brought by installation as an art form is the wonderful sensation of almost, but not quite, grasping the fundamental truths of the world with a side effect of incomprehensible beauty. The first relies on leading the spectator through a successive series of events, the latter on setting the spectator free to form his or her own quasi-narrative. Of course I am nowhere near obtaining those two things at the same time, but it actually is what I am striving for, the artistic drive, that make me want to make the next piece, always. It may sound impossible, beside the point, or pompous even, but I think it is good to have goals that are hard to reach.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: ”Relief” has three variations inside around a powerful central concept: it could be translated as: a) the human metamorphosis due to a personal choice b) the scientific sense c)the geopolitic sense. In all of these three meanings the figure of Nabokov is like a conjunction, a symbolic metaphora such as Ukraina. Could you express the starting point of the work? Do you consider it a politic work?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: First came the ambition to make a piece about the geopolitical/cultural changes that happen in the active zones around the edges of well-defined entities (Europe/Russia). This was broadened to the abstract concept of the relief that of course has the somewhat disturbing dual meaning of something in-between and something clarified. Nabokov intuitively became a good friend in this field, since he, as you rightly put it, functions as a conjunction, he is an entity that functions well in these overlapping fields of sense, riding comfortably the agitated space between and on the dual concepts of reality/fiction, science/art, east/west, and belonging/annihilation. He seemed to provide a position where these pairs of concepts were no longer mutually exclusive, but rather different aspects of the same preoccupation. It is a political work because it is subjective, trying to develop an attitude on big issues, not because it tries to transmit a fixed message. In the end it is still up to the individual spectator to form his or her own opinion.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: In Relief you used 3D animation, historical images from the archives and interviews from the street and the actor as human being (the character Nabokov). Is it for making clear the different degrees of reality, the duality between reality/fiction? Do you think, in this case that the meaning is clear enough to the audience?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: We tend to consider Film more real then Drawing. History more real than Anecdote. Passers by in the street more real than Actors, even though this is not necessarily so. Everything is real, you can only argue for a gradual relation to referential objectivity. So what you consider real is a matter of personal opinion. My hope was to make people see the reality of this, if not in an intellectual sense, then hopefully on a more subconscious level. I certainly don’t think that this meaning is clear to the audience, I rather think, that what they previously thought was objectively real is now a little bit more obscure.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: In the notes you speak about the importance of different levels of perception and during the show you used 3d sound, headphones for audience, and sophisticated audio-video systems. Is the “immersivity” through all the senses the real objective of the show?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH: If I drop a glass to the floor in front of you, you see the glass break and hear the breaking sound simultaneously. If you see the same thing on film, I can make the two cognitive inputs break apart, thus clarifying the artificiality of the media. It is difficult, if not impossible, to not think that either the visual or the acoustic input is the true happening and that the other is either too early or too late. Which event you consider true is highly individual. I split up sound and image to play with one of the most basic relief phenomena, that of similarity between visual and acoustic information. As the play moves on, the audience in general hopefully gives up comparing the two information and become immersed in the collected sensory information available. This is a clear objective, give up thinking and start sensing, but it is not the purpose of the piece, just another way to construct it.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: Hotel Pro Forma made a show about Andersen, also Robert Lepage did it and also Lepage was inspired by a biographical episode not so known, like you. Did you see this Lepage’s work? What is your opinion?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH. I did see it, yes, and I also rather liked it, it was very playful and imaginative. Using Andersen is just as much a pretext, for Lepage as well as for us, a kind of giant McGuffin to access other areas of interest such as narration, theatre and imagination in the case of Robert Lepage, and individuality, travel, and imagination in the case of our production.

ANNA MARIA MONTEVERDI: The digital performance will substitute the traditional theatre?

RALF RICHARDT STRØBECH. I hope not! but I guess that the distinction will gradually diminish as traditional theatre will incorporate more and more technology, and, hopefully, digital performance will stop distinguishing itself so much from the classical, as I mentioned before there is merit in both fields. It is important that we learn from each other instead of creating artificial and fruitless wars.

More: Hotel Pro Forma: Nomadic Theatre Without Borders? by MILDA OSTRAUSKAITE